Nature vs nurture: which can be seen as predominant in natural wine and what could be said to be the main differences with conventional wine?

Natural wine for me was born as a very noble idea, indicating all those wines made without excessive intervention both in the vineyard and in the cellar. Of course once that, after the hard work of a handful of pioneer vignerons in the very beginning and many others afterward, this idea started becoming more and more popular, the conventional/industrial side of the wine industry decided to intervene, or counter-attack in a way. They lobbied to ban the use of the term on labels and in any official capacity, so you have for example pasta and baked goods multinational Barilla being able to write on their cookies’ packaging that they make “natural cookies” but Radikon cannot say they make “natural wines”.

You can say it without consequence but you cannot write it, correct?

Yes, writing it can have very serious consequences, such as heavy fines – among others. I’ve pretty much stopped even using the term, while in the past I often did. This is mostly to avoid misunderstandings like “natural wines are not made by themselves”, “natural wine cannot age” and all such nonsense.

Do you still use the term with wine-lovers that know your wines and with friends? That is, with people that know exactly that the term simply indicates a set of practices in the vineyard and the cellar.

In that case, I still do actually, just because it’s simpler to do so when I’m talking to people, like you for example, that have a background in this sense and that know exactly how we work and what our philosophy is. When it was born the term “natural wine” was beautiful, and it could and did mean many things along with the technical aspects. It encompassed an ethical dimension that focused on the wine itself but also nature, the environment, and the terroir.

It should never be overlooked that, to make natural wine we “make use” of our land and terroir, and the more we respect the land and the kinder we are to it the better the wine will be and the more realized all the ethical dimensions I mentioned. Today the term has in a way been emptied.

Let me tell you a story: I just purchased a small vineyard close to our home, which was semi-abandoned by the previous owner. He hadn’t done any kind of maintenance for years, including natural treatments, resulting in the weaker vines suffering quite a lot. The surrounding woods were invading the vineyard to the point that the vines didn’t have enough air to breathe. Parts of the trees were dangerously dangling over the nearby road, so anyone passing by in a vehicle could be seriously injured, or worse. This just goes to highlight how respect for the land and terroir is of paramount importance, allowing us to work for our sustenance but also for the community and for those that will come after us.

Those who know and love your wines, and know the way you and Stanko always worked, know just as well that it’s implied that we’re talking about natural wines. However, a debate you see going on, mostly in Italy truth be told as opposed to export markets, is that which focuses on the asserted misleading nature of the term. Meaning that it might lead some to believe that we’re talking about wines that come to be through some sort of miracle and with no human intervention. Some argue that the term “artisanal wines” might be more appropriate. What’s your take on this?

“Artisanal wines” is just as misleading and a very poor substitute at best. It will never be appropriate: the huge industrial operation producing 1 million bottles could easily argue that their processes are “artisanal” and they could well be if they have the finances to invest. Even if you add a bit of SO2 you cannot argue that you’re not adding anything to the wine. Also, you could have a tiny winery, maybe producing 3,000 bottles per year, and they could very well “artisanally” and by hand do all those things that will make them not natural, such as using chemicals in the vineyard, fermenting with selected yeasts, fining, sterile filtering and so on.

I’ve personally seen winemakers I know, producing no more than 6,000 bottles, spraying tannins on the vines during harvest to avoid the risk of oxidation. The list goes on with commercial yeasts, filtering, and so on…

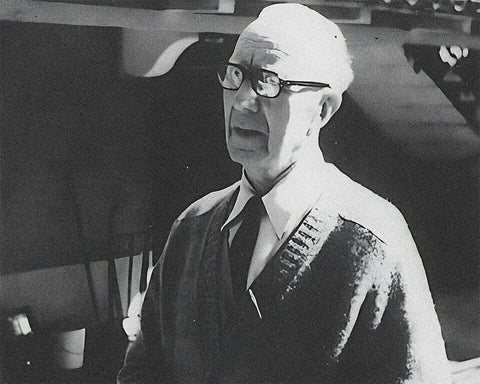

I’ve heard your story on more than one occasion but every time you tell me new precious nuggets and details emerge. Going back to basics though: was it your father Stanko that officially started selling the wines as Radikon or was it your grandfather?

Depends on what you mean exactly, although the correct answer is probably that my father started. My grandfather did sell some wine, but it was strictly in bulk to 2-3 local restaurants. It was my father who, while continuing with bulk wine, started selling bottled wine, with the first official vintage being in 1979.

Holy crap, 1979! Probably the oldest of your bottles that I saw was last year in Japan, in the personal collection of Hisato of Vinaiota (Radikon’s Japanese importer, a true pioneer in spreading the natural wine verb).

That doesn’t surprise me at all: he probably has more rare and old vintages of our wines there than we do ourselves. As you well know he’s one of the biggest import partners for us, if not the biggest one. And aside from that, he’s a dear friend and one of the most kind-hearted people I know.

I cannot but agree with you on that: he’s one of the nicest people around, a veritable hero in my opinion in the natural wine world. Not only commercially, since I think he moves maybe more than ½ a million bottles per year or so, but also culturally, as he began in the late 90s and greatly contributed to making Japan undoubtedly the most advanced natural wine market in the world.

Indeed! And he’s one of the most formidable palates around, along with having a monumental wine culture.

So it’s been about 40 years since your father started bottling in 1979. And about 15 years about that your father converts to the natural wine way, correct? I have 1995 as a date that is stuck in my mind, was that it?

Yes, it was indeed 1995, although we had been working organically in the vineyard since we began. In 1995 my father vinified our Ribolla with maceration on the skins for the very first time.

What was the spark that prompted this radical turnaround?

In reality, there were several sparks. Let me first say that when we speak of a specific development in the wine world we must pinpoint and understand the historical context in which it happened, and what has now changed since that time. In the 1980s my father, after many sacrifices, started to make something like serious money with the winery, with all profits being re-invested in the business. Rather than buying a new car, he bought steel tanks, a new press, and so on. He, unfortunately, got rid of the old wooden barrels my grandfather used since that was the modernizing trend in the wine world at the time. Their demise is something that I regret since those barrels were still good and could have contributed much to the wines.

What made a difference at that point was the switch from the old manual press to a brand new pneumatic press. The mechanism of soft-pressing led to the extraction of much fewer tannins, which back then was considered a stylistic plus. So from one day to the other everything changes: even when direct-pressing, the higher pressure of a manual press does extract a measure of tannins. As this element changed, the wines themselves changed drastically, becoming much lighter, ethereal, and some would say more elegant but much less characterful and flavourful.

This difference was particularly evident with our Ribolla, the variety that my father always favored and championed. Just like my grandfather, he put Ribolla on a pedestal and considered it our most important and representative variety. The only condition that my grandfather put to hand down the winery to my father was that the parcels with the best soils and exposition could be only planted with Ribolla. Ribolla is characterized by a very thick skin, where a lot of its flavor and aromatics reside, and when you press it with a soft pneumatic press you extract much less of its character than you would with a manual press.

So, this first spark can be summarised in a question that my father asked himself: why the broad range of flavors and aromas that I used to perceive in my Ribolla is now completely gone? And keep in mind that we’re talking about the pre-maceration era.

So, both on the nose and the palate, we were dealing with a different wine?

Absolutely! He felt something was radically wrong, although we didn’t immediately associate the difference with the switch to the soft pneumatic press. Something was missing and my father had the intuition to go back to tradition and to my grandfather's way of doing things. You need to understand that maceration was then somewhat unthinkable, and my father was making “classical” wines that obtained both commercial and critical success. Including the “Tre Bicchieri” award from Gambero Rosso that he first won in 1988, at a time when those types of awards carried considerable influence. And we won with what? With Merlot? The question here is: why do they appreciate our Merlot and not our whites? Especially our Ribolla, which is the empress among our varieties. Could it maybe something related to maceration, since all of our reds (as all reds do) saw considerable skin contact while none of the whites did?

So the idea took shape of treating white grapes like red ones, correct?

That’s right, the idea was born and consolidated relatively quickly, especially after many conversations on the topic with my grandfather. This technique was quite the traditional one in these hills and my grandfather had always used it. Probably not so much to gain more extraction but more for the sake of simplicity and convenience. My family back then harvested those 1-2 hectares we farmed at the time within 3-4 days and gradually took the grapes to the cellar. They put the grapes in wooden and glass fermenters and they stayed there for a few days, fermenting spontaneously on the skins until they had time to press the must.

Incidentally, those homemade wines were both delicious and surprisingly stable and long-lived. My father then single-mindedly focused on rediscovering the true flavor of Ribolla through this old/new technique. This was our new beginning in 1995. Of course, we shared our experience with friends and colleague winemakers, and some decided to adopt this new way of working. The most famous one is Josko Gravner, who started with macerations in 1996, though he arrived at this decision through a different journey and process.

That’s right! And a few years later came his famous Georgian trip and the adoption of amphorae.

Yes, I think we’re talking about maybe the year 2000 or so, but he had already started using skin contact years before that. His reasoning and philosophy around maceration were quite aligned with my father’s, and that’s also why they became so close, though later unfortunately they grew somewhat estranged.

Did Stanko experiment with different lengths of skin contact? How was it that he found his way?

He did indeed. Now we macerate for about 3-4 months, depending on the vintage’s characteristics, and in recent vintages, it’s been more like 3 than 4. We did experiment quite a bit beginning in 1995, initially with shorter macerations of 1-2 weeks, then extending to 8 months and even one full year. The one-year maceration experiment was super interesting – in the year 2000, long maceration for Tocai (it had stayed on the skins until late in the Spring and the results were very nice, then unfortunately we had a fermentation anomaly and that was the end for that wine).

We think now that pressing the wine off the skins when it’s becoming too hot can cause problems. We found out through experience that pressing in the Winter brings out the best in the wine. Of course, a more extended maceration allows you to play with longer elevage: we found that with, for example, a one-month maceration the wine’s not yet mature (with much extraction but incomplete in refinement), while with 3-4 months, extraction is optimal and the wines are ready to be pressed in the winter. In this phase elevage in large barrels becomes extremely important, since the longer maceration allows the wines to be softer and more ready for aging in wood and subsequently in the bottle.

Going back to super-long macerations, another thing we’ve observed is that a one-year maceration leads to wine becoming somewhat “impoverished”, less vibrant, and much thinner. Interestingly enough wines with a longer 6-8 months of maceration are ready to drink much sooner compared to ours, they’re wines that are ready and finished within one and a half years. They do, however, often lack something both in structure and in agility on the palate; therefore I believe that 3-4 months is the sweet spot for us. At least it’s the sweet spot for what we want to achieve.

A bit more of a provocative question: personally, and I imagine it’d be the same for you, it happens very very rarely to drink conventional wines. I certainly wouldn’t spend any money on it but, whether it’s an event or a dinner, at times it can happen. Well, on one occasion I almost imposed it on myself as a didactic experience. I did taste 2 conventional, non-skin contact Ribolla, and… I don’t remember which wine or winery (and if I did I wouldn’t name them), but they pretty much tasted like water. No taste or character to be found. What is your view or experience on this?

Of course, it’s a matter of personal taste and cultural outlook but I’d say my views on this are quite aligned with yours. And this is especially evident with the prestigious, award-winning Ribolla grape varietal. No matter what, you have some sort of high expectation and, after a barrage of simple, sweet aromas, what little you have on the palate is so evanescent that it’s gone after a few moments. I see a complete lack of structure and tension.

Maybe all aromas and no taste?

Exactly! We should also recognize that an important factor here is that our palate has changed enormously. Those wines (made conventionally) are made to be forever immutable, it is we who have changed. They have their public and we have ours, and they rarely if ever intersect.

The change to drinking natural can be gradual or sudden. In my case, it was quite sudden, as I was converted to natural wines (and orange wines) in the mid-2000s in Japan with your wines and those of Dario Princic. And once you embark on that path you never go back.

I completely agree, I’ve never seen anyone going back actually. That said, there can be some very interesting conventional wines, but we’re talking about very old vintages, where the difference with natural wine was not so abyssal. That’s also because the exasperated use of invasive techniques in the cellar and chemicals in the vineyard is something relatively new in wine if we take the long view. Before their arrival, you had on average very good and often wonderful wines.

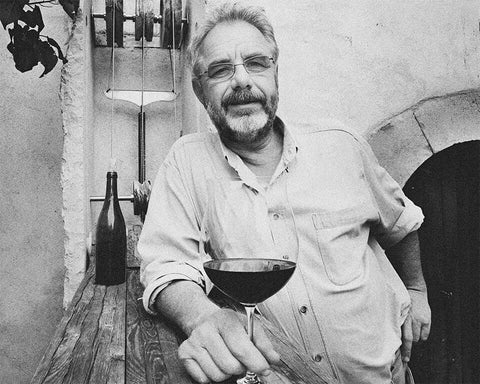

We discussed this before but I think it could be interesting to shed further light on it: what has changed in the vinification at 2 stages? The first is when you first introduced your line of fresher, less macerated wines, Sivi and Slatnik, and the second is when you took the helm of the winery after your father’s sad passing.

Everything changes with every vintage in a way, as each vintage has its personality. Everything here’s in a constant state of flux, so I cannot say that I make wine the same way my dad used to. My father firmly believed, as do I, that every harvest had real meaning only if it thought us something new. Let me give you a simple example: the 2017 vintage had been a perfect one here in Collio and Slovenia’s Brda, the ideal vintage under all aspects; then on the 9th of September it starts raining and keeps on going for 14 days. This was something that had never happened before. What do you do in such a case? You do what you can and try to handle the situation based on your knowledge and sensibility. By mid-October, there were hardly any leaves left on the vines, it was quite cold and the vines severely lacked light, so the vines, under stress, tried to extract as many nutrients as possible from the soil through the roots. The wines are rather interesting but will probably need longer than usual to be released. So, every harvest is most definitely always a learning experience.

Coming now to the “S line” of wines, Slatnik and Sivi, I began in 2009, when in Italy at least there was no such thing as an orange wine trend. There was a minority who appreciated them and many drinkers who didn’t understand them or rejected them. I felt there was a large section of young drinkers – I too was very young at the time – who were curious but needed a bridge, and introduction to macerated wines. It could happen that such drinkers maybe fell in love immediately with our wines, but many were still puzzled.

So I set out to find a “softer” path to macerated wines, which meant doing what my father had done during the experimental phase: using macerations of 1-2 weeks, targeted on varieties that could be exalted by them. So the first step was creating the Slatnik, at the time made up of Chardonnay and Friulano, followed by Pinot Grigio, which my father had never vinified with skin contact.

This was the very first project in which I would make wine completely on my own, and it was a great gesture on my father’s part to let me go my own way with this wine. He also recognized that we needed to evolve and attract also a wider, younger range of drinkers. He also helped and overviewed, but the final decisions were mine and mine alone. We were a bit hesitant about announcing this new project initially, so it was kept secret for a while, for maybe one and a half years, when we felt the wines were ready and had come into their own.

Whid did you decide, for these new wines, to use the more common 750ml bottle format, rather than the 1l and 500ml used for the other wines? Was it to make them more approachable to a casual, non-expert drinker?

Yes, that was the reasoning. Since the aim was to introduce a wider audience to natural and orange wines, we placed in front of them something that looked more familiar: a younger vintage and a more normal-looking bottle. Also, the idea was to make a wine to be drunk relatively young, and the 1l bottle was born for long aging, even after release. I’m not saying that the "S" line can’t age but it’s a line of wines created to be drunk within maybe 2-3 years.

This is quite interesting since I was lucky enough to find in Japan older bottles of both wines, often served by the glass, and they always showed beautifully.

That’s true, although we couldn’t know that for sure at the time. When I took over the winery after my father left us, I can say I most definitely followed in his footsteps, which were also partially mine, but of course, also added my elements of insight. And since with every vintage you learn something new, we always make incremental changes and modifications. Our increase in size here has become an important factor: just think that my father used to farm and vinify 12 hectares, this vintage it’s 19 and next year it will be 25.

This growth has made sense, since it’s part of a long-term plan where we purchased and planted new vineyards, patiently waiting for when they could be productive. The market also demanded it and, by gradually increasing, we can keep a more stable pricing system. My target is to produce consistently every year about 80-100,000 bottles maximum, which at the moment I cannot yet do. That’s probably the ideal size given market demand and growth but especially what I can farm and vinify artisanally following my system and philosophy.

Talking about market demand, one question came to mind. My feeling is that, since I work in many export markets, you’ve long since reached such an iconic status that, were you to even exponentially increase production, most markets would just lap it up happily and ask for more. Do you share this feeling?

I’m not quite sure about all or most markets but, when it comes to a few strategic ones, it’s fairly close to the truth. Vinaiota in Japan regularly buys about one-fifth of total production, maybe 10-15,000 bottles per year. He’s often told me that he could easily buy 7-8 times that volume.

This is amazing especially because, and we’re talking about the largest natural wine market in the world, the yearly per capita wine consumption is only about 4 liters, which is probably what you or I drink in a week or so. Yet natural wine is so widespread that it’s difficult to enter any kind of restaurant in Japan, regardless of how remote a location, type of cuisine, or price point, and not find natural wine. To me, Japan is a bit of the arrival point or aspiration for natural wine markets, where natural wine is completely normalized and mainstream. This leads us to the next question: how have you seen the market change over the years, both when it comes to wine professionals and wine lovers?

Regarding the Japanese market, I have visited many times with Hisato and witnessed firsthand how widespread the love for natural wine is, as this had been introduced in the market back in the late mid-1990s. The 2011 Fukushima incident was also an event that, according to what Hisato told me, marked a radical change, a paradigm shift in the Japanese people’s way of thinking. Though this attitude existed before, now it became widespread: most people realized that they had to give new value and great attention to sustainability and environmental issues, and they did this with the focused resolve that is typical of the Japanese.

They applied this to every aspect of life, from buying groceries to buying wine. That’s one of the reasons why I think Japan is much more evolved than here in Italy, and there is much more awareness and attention to what products are purchased, both when it comes to sustainability and cultural value. But it’s about sustainability as much as taste. Since umami is such an important element in Japanese cuisine, I believe their palate is also more evolved, while here in Europe but especially in Italy this concept was unknown until very recently.

Japanese people know well and deeply appreciate umami, which is such a big part of the taste spectrum of natural/orange wines, and they can find it and appreciate it in wine. Here (in Italy) many palates are anesthetized by the chemicals and additives in both food and wine. Especially when it comes to wine, years of conventional wine gustative “indoctrination” has led many drinkers to expect very few, recognizable and overly simple aromas and almost no taste.

To this day in Italy is still very difficult to find a restaurant where all or the majority of the food is organic, let alone an all-natural wine list. On the contrary, in Japan, as well as large cities in the US or Nordic countries, this is commonplace. This is probably due to the enduring belief here that working organically is not economically sustainable. Our taste buds have become drugged and unable to recognize and appreciate the taste of an organic home-farmed tomato. Chemical fertilizers and pesticides have made it so that you have these perfect, shining, and blemishless tomatoes. Then you bite into it and you have no idea whether you’re eating a tomato or an apple.

That’s true with wine as well, with a conventional Ribolla tasting just like a Vermentino or Trebbiano. In my view and experience, the rise and growing popularity of the natural wine movement has resulted in a re-discovery of flavors in wine and of wine’s cultural significance. Talking about the movement, when I organize or speak at seminars the question often arises about whether natural wine is a fleeting fad or an enduring phenomenon. It’s funny because in Japan it’s been a fleeting trend for over 25 years, in the US and Denmark maybe 10-15, and the list goes on.

Speaking about Denmark: I visited only once years ago for a natural wine tasting and I happened to book the hotel very last minute, pretty much random. What truly amazed me was that, when I went down for breakfast in the morning, the first thing I saw was a sign saying “everything that you will be served here is organic”. We have a B&B and we try to source only organic produce and foodstuffs, it’s very hard in Italy but it’s doable. The crazy thing is that often it doesn’t meet the guests’ taste, they just don’t understand it.

They don’t understand that real cornflakes just do not taste like commercial cornflakes. But, and this is, of course, true also of natural wine, once you do get hooked to real taste there is no turning back, ever. In Italy there is also a matter of high costs: since organic products are less common they tend to be much more expensive and the average family can only afford them on occasion. The ultimate truth in my view is that, aside from the environmental aspects, natural wine cannot be a temporary fad because it just tastes so much better.

Last couple of questions: I’m sure you know about the natural wine legislation that recently passed approval and is now in force in France. And it’s a very well-made law in my opinion, with reasonable and stringent parameters. How do you see the debate on the need for EU or Italian legislation on natural wine? And how do you see the natural wine movement and markets developing in the future?

I’m very pessimistic about the possibility of adequate legislation on natural wine. It would just be way too difficult: our political class and the forces of the conventional wine industry would never let us work towards true natural wine legislation. Natural wine today unfortunately is such a tiny niche in the wine sector that it has very little lobbying influence. It’s a niche, however, that is seen as threatening, therefore the conventional giants would never allow for true legislation to be passed, formally recognizing natural wine as such.

Recently they even banned the word and concept of “biodynamics” from the "ecological transition" law being debated in Parliament. This means that we are most definitely seen as a threat. The argument was that it’s an anti-scientific concept, but it ignores several academic studies pointing to the scientific mechanisms at the core of biodynamic practices. Despite this, I see the movement as enduring, growing, and prospering because natural wine drinkers have much more awareness as far as the environment, and sustainability – and just have a better palate. Conventional wine drinkers will continue to drink conventional and it’s right for them to do so if they wish. But they will never escape from the bubble they live in.

I’m sure both you and I know scores of people who, once converted to drinking natural wine, started to drink only natural wine and never went back to conventional. I never met anyone who said, “I’m fed up with natural wine, I don’t like it anymore and I’m going back to drinking conventional.”

Absolutely! I never met anyone who abandoned natural wine for conventional. For me, even one single person that converts to natural wine is a cultural victory.