Provence has a rich winemaking history spanning thousands of years with its fields of lavender, garrigue, rugged coastlines, and alpine scenery. This southeastern French region is renowned for producing a variety of wine styles, yet it is most celebrated for its crisp, refreshing rosés. These wines capture the essence of Provence's unique terroir and climate. To fully appreciate the significance of Provence's wine, it's essential to delve into the region's rich history of winemaking. This southeastern corner of France has been cultivating vines for thousands of years, influenced by various cultures and civilizations that have shaped its wine heritage.

The Founding of Massalia: A Turning Point in Provençal History

In the early 6th century BCE, a group of brave Greek sailors from the city of Phocaea in modern-day Turkey set out on a journey that would change the course of history in southern France. These Phocaeans, known for their seafaring prowess, were looking for new trading opportunities and, perhaps, a place to call home away from the growing threat of Persian expansion in their homeland.

Around 600 BCE, their ships entered a natural harbor on the Mediterranean coast of what is now France. With its protective limestone cliffs and defensible position, the site must have seemed ideal to these experienced mariners. This was the birth of Massalia, known today as Marseille.

Legend has it that the founding of the city involved a romantic twist. The story goes that the leader of the Greek expedition, Protis, arrived on the day the local Ligurian king was to choose a husband for his daughter, Gyptis. During the feast, Gyptis was to present a cup of wine to the man she chose as her husband. To everyone's surprise, she offered the cup to Protis, the foreign newcomer. This marriage allegedly sealed the deal, allowing the Greeks to establish their settlement with the blessing of the local tribe.

While this tale adds color to the founding of Massalia, the reality is likely more complex. Archaeological evidence suggests that there was already a native settlement in the area when the Greeks arrived. The integration of the newcomers involved a mix of diplomacy, trade agreements, and some conflict.

What's certain is that the establishment of Massalia marked the beginning of a significant Greek presence in the region. The Phocaeans brought with them not just their ships and trading goods but also their culture, language, religious practices, and, importantly for our story, their knowledge of viticulture and winemaking.

The Greeks had long cultivated grapes and produced wine in their homeland, and they wasted no time in introducing these practices to their new settlement. They planted vineyards on the sunny slopes surrounding Massalia, taking advantage of the Mediterranean climate similar to their native land.

This introduction of systematic viticulture was a game-changer for the region. While wild grapes likely existed in Provence before the Greeks arrived, the Phocaeans introduced the techniques of large-scale cultivation and winemaking. They brought grape varieties from their homeland and the knowledge of how to tend the vines, harvest the grapes and ferment them into wine.

The impact of this cannot be overstated. Wine quickly became an essential part of the local economy for local consumption and trade. The Massaliotes (as the inhabitants of Massalia were known) traded their wine along with other goods like olive oil and salt fish, extending their influence along the coast and up the Rhône valley.

But the Phocaeans brought more than just wine. Their arrival marked the beginning of urbanization in the region. Massalia grew into a prosperous city-state with its coins, a complex system of government, and impressive public buildings. It became a center of Greek culture in the western Mediterranean, influencing the surrounding indigenous populations and acting as a conduit for Greek ideas, technology, and trade goods.

The founding of Massalia by the Phocaeans around 600 BCE was a pivotal moment in the history of Provence. It set in motion a chain of events that would shape the region's culture, economy, and wine industry for millennia. The legacy of those intrepid Greek sailors can still be felt today in the vibrant city of Marseille and every glass of Provençal wine.

Introduction of viticulture and winemaking techniques

When the Greeks first laid eyes on the sun-drenched hills of Provence, they must have seen a familiar sight. The Mediterranean climate closely resembled their homeland with its hot, dry summers and mild winters. It took a little while for these experienced vintners to recognize the potential for grape cultivation in their new territory.

The Greeks brought with them not only their knowledge but also vine cuttings from their native land. These were likely varieties of Vitis vinifera, the species responsible for nearly all of the world's wine grapes today. While wild grapevines probably existed in Provence before the Greeks arrived, these imported varieties and the techniques to cultivate them laid the foundation for the region's wine industry.

One of the Greek settlers' first tasks was to clear land for vineyards. They chose sunny, well-drained slopes, often terracing hillsides, to maximize exposure and minimize erosion. The Greeks understood the importance of proper vineyard management, introducing techniques such as pruning to control vine growth and improve grape quality.

The timing of the grape harvest, or vendange, was crucial. The Greeks brought with them the knowledge of assessing grape ripeness, likely using a combination of visual cues, taste, and perhaps even primitive forms of measuring sugar content. This ensured that the grapes were picked at the optimal time for winemaking.

Once harvested, the grapes were typically crushed by foot in large vats. The Greeks introduced lever presses to extract more juice from the grape skins, a technique that allowed for greater efficiency in wine production. Fermentation would have occurred in large ceramic vessels, with the natural yeasts on grape skins converting the sugar in the juice to alcohol.

The Greeks also brought the concept of aging wine to improve its quality. They used amphorae, large ceramic vessels, to store and transport wine. These were often sealed with pine resin to prevent oxidation, a practice that likely influenced the taste of the wine and may be an early precursor to the Greek retsina style.

Interestingly, the wines produced in this early period were quite different from what we associate with Provence today. They were likely strong, sweet, and often diluted with water before drinking. The production of lighter wines, particularly the pale rosés that Provence is famous for today, would come much later.

The impact of Greek viticultural knowledge extended beyond just the production of wine. They introduced the cultivation of olives alongside grapes, establishing the Mediterranean triad of wheat, olives, and grapes that would define agriculture in the region for millennia.

As Massalia grew and prospered, so did its wine trade. The city became a significant wine production and distribution center, with Provençal wines being traded along the coast and up the Rhône valley. This trade helped spread both the product and winemaking knowledge to other parts of Gaul.

The techniques introduced by the Greeks laid the groundwork for all future winemaking in the region. Even as the Roman Empire later expanded into Provence, bringing its innovations, the fundamental practices established by the Greeks remained. The Romans built upon this foundation, expanding vineyard plantings and introducing new grape varieties, but the essence of Provençal viticulture remained rooted in these Greek beginnings.

Some 2,600 years after those first Greek vines were planted, Provence remains a vital wine-producing region. While techniques have modernized and grape varieties have changed, the essence of Provençal wine can be traced back to those Phocaean settlers. Whenever we open a bottle of Provençal wine, we taste the fruit of an ancient legacy that began with the Greeks and their introduction of viticulture to the sun-soaked hills of Provence.

Establishment of the first vineyards along the coast

As we've explored in previous paragraphs, the arrival of the Phocaean Greeks in Massalia around 600 BCE marked the beginning of systematic viticulture in Provence. But where exactly did these pioneering vintners plant their first vines? The answer lies along the Mediterranean's sun-drenched coastline, where Provence's first vineyards took root and flourished.

The choice of coastal locations for the first vineyards was no accident. With centuries of viticultural experience, the Greeks recognized the unique advantages that the Provençal coast offered for grape cultivation. The Mediterranean climate features hot, dry summers and mild winters, closely resembling the conditions in their homeland. Moreover, the coastal areas provided several key benefits, making them ideal for establishing vineyards.

Firstly, the proximity to the sea moderatingly influenced temperatures. The Mediterranean acted as a thermal regulator, preventing extreme temperature fluctuations that could damage the vines. This microclimate was particularly beneficial during the critical growing season, allowing for even ripening of the grapes.

Secondly, many coastal areas in Provence feature limestone-rich soils. While challenging for many crops, this type of terrain is excellent for grapevines. Limestone soils provide good drainage, forcing the vines to drive their roots deep in search of water and nutrients. This struggle results in lower yields but often higher-quality grapes with more concentrated flavors—a principle that remains crucial in fine wine production to this day.

The hills and slopes near the coast also played a crucial role. As mentioned in our discussion of Greek viticultural techniques, these settlers were adept at terracing hillsides to maximize sun exposure and minimize erosion. The undulating coastal landscape of Provence provided ample opportunity to apply these skills, creating vineyard sites that captured the most sunlight and the cooling sea breezes.

Roman Influence on Provençal Viticulture: Expansion and Innovation

The arrival of the Romans in Provence in 125 BCE marked a new chapter in the region's viticultural history. While the Greeks had established a thriving wine culture along the coast, as we've explored in our previous discussions, it was the Romans who would take viticulture in Provence to new heights, quite literally pushing it inland from its coastal roots.

The Roman conquest of Provence, or Provincia Romana as they called it (giving rise to the region's name), was driven by strategic interests. They sought to secure a land route between Italy and their territories in Hispania (modern-day Spain). However, the Romans quickly recognized the region's economic potential, particularly in terms of wine production.

Spread of Viticulture Inland

Unlike the Greeks, who primarily confined their settlements and vineyards to the coast, the Romans took a different approach. They saw the potential in the inland areas of Provence with their diverse terroirs and microclimates. The Romans began establishing colonies and settlements throughout the region, each accompanied by new vineyard plantings.

The famous Roman roads facilitated this inland expansion of viticulture. As they built their well-engineered roads across Provence, they inadvertently created corridors to spread viticultural knowledge and grape vines. Settlements along these roads, such as Aquae Sextiae (modern-day Aix-en-Provence) and Arelate (Arles), became new centers of wine production.

The Romans also introduced vineyard plantings to the Rhône Valley, pushing wine production northward. This expansion laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the renowned wine regions of the Southern Rhône, including Châteauneuf-du-Pape and Gigondas.

Introduction of New Grape Varieties and Cultivation Techniques

The Romans brought a wealth of viticultural knowledge from across their vast empire. They introduced new grape varieties to Provence, some of which may still be found in the region today. For instance, it's believed that the Romans introduced Muscat to the area, a grape that plays a role in several Provençal wines, particularly in the sweet wines of Beaumes-de-Venise.

Roman agricultural writers like Columella and Pliny the Elder documented extensive knowledge about viticulture. They introduced more systematic approaches to vineyard management, including advanced pruning techniques and training vines on wooden frames, a precursor to modern trellising systems.

The Romans also refined the understanding of how different soils affect wine quality. They categorized lands based on their suitability for viticulture, a practice that laid the groundwork for the modern concept of terroir. This knowledge allowed them to successfully establish vineyards in diverse inland areas of Provence, each producing wines with distinctive characteristics.

Development of Amphora Production for Wine Transportation

One of the most significant Roman contributions to the wine industry in Provence was the development and refinement of amphora production. While the Greeks had used amphorae for wine storage and transportation, the Romans took this craft to new levels of sophistication and scale.

Amphorae were large clay jars used for fermenting, storing, and transporting wine. The Romans established numerous pottery workshops throughout Provence dedicated to amphora production. One of the most significant was located in Marseille, where archaeologists have uncovered the remains of large kilns and countless amphora shards.

The standardization of amphora design was a key Roman innovation. They developed specific shapes and sizes optimized for wine transportation, some capable of holding up to 100 liters. These standardized containers revolutionized the wine trade, allowing for more efficient storage and transport across the empire.

The Romans also improved the sealing techniques for amphorae. They used cork stoppers sealed with pitch or resin, allowing for better wine preservation during long-distance transport. This advancement enabled Provençal wines to be shipped across the Mediterranean and beyond, significantly expanding the market for local vintners.

Interestingly, the Romans also began to label their amphorae, marking them with details about the wine's origin, vintage, and even the producer's name. This practice can be seen as an ancient precursor to modern wine labeling and appellation systems.

The Roman period saw Provençal wine production evolve from a primarily local industry to one capable of serving markets across the empire. The inland expansion of vineyards, coupled with new varieties and techniques, diversified the styles of wine produced in the region. Meanwhile, advancements in amphora production and transportation networks allowed these wines to reach a wider audience.

Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Winemaking in Provence

The rich history of viticulture in Provence, from the arrival of the Phocaean Greeks to the expansive influence of the Romans, is not merely a tale passed down through generations. It's a story etched into the very earth of the region, waiting to be uncovered by the careful hands of archaeologists. Provence's archaeological evidence of wine production provides tangible links to our previous discussions, offering concrete proof of the region's ancient viticultural heritage.

Discovery of Ancient Wine Presses and Storage Facilities

One of the most exciting aspects of archaeological research in Provence has been the discovery of ancient wine production facilities. These findings provide invaluable insights into the scale and techniques of winemaking in antiquity.

Archaeologists have unearthed several Greek-era wine presses in the hills surrounding Marseille dating back to the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. These presses, carved into the limestone bedrock, consist of shallow basins where grapes were trodden by foot. Channels carved into the rock guided the juice into collection vats, where it would ferment into wine. The discovery of these presses corroborates our earlier discussions about the establishment of the first vineyards along the Provençal coast by the Phocaean Greeks.

Roman-era wine production facilities have been found throughout Provence, reflecting the inland spread of viticulture we discussed earlier. A particularly well-preserved example was discovered near the Roman town of Glanum (near modern-day Saint-Rémy-de-Provence). This facility includes presses and large dolia – enormous ceramic vessels used for fermenting and storing wine. These findings illustrate the more advanced winemaking techniques introduced by the Romans and the larger scale of production compared to the earlier Greek period.

Examination of Recovered Amphorae and Their Inscriptions

Amphorae, the ceramic vessels used for storing and transporting wine that we discussed about Roman innovations, have proven to be a treasure trove of information for archaeologists. Thousands of amphora fragments have been recovered from sites across Provence, with many complete vessels found in shipwrecks off the coast.

Studying these amphorae has revealed much about the wine trade in ancient Provence. Different shapes and styles of amphorae have been linked to specific production regions, allowing archaeologists to trace trade routes. For instance, distinctive amphorae produced in Marseille have been found as far away as Carthage and Rome, demonstrating the extensive reach of the Provençal wine trade.

Perhaps most excitingly, some recovered amphorae bear inscriptions that offer direct glimpses into the ancient wine industry. These inscriptions, usually stamped or painted onto the amphora before firing, can include information such as:

- The name of the wine producer

- The place of origin

- The type of wine

- The year of production (especially in the Roman period)

One fascinating example is an amphora found in the ancient port of Marseille, bearing an inscription in Greek that translates to "Fine wine from the vineyards of Pytheas." This confirms the production of high-quality wine in the region and provides a personal connection to an individual vintner from over two millennia ago.

Analysis of Pollen Samples Indicating Widespread Grape Cultivation While structural remains and artifacts provide valuable information, some of the most compelling evidence for widespread grape cultivation comes from a much smaller source: pollen. Palynology, the study of pollen grains and spores, has revolutionized our understanding of ancient agriculture in Provence.

Pollen samples taken from ancient lake beds and soil cores throughout Provence have revealed a significant increase in Vitis (grape) pollen coinciding with the arrival of the Greeks in the 6th century BCE. This spike in grape pollen, which continued and intensified during the Roman period, provides clear evidence of extensive vineyard plantings. What's particularly valuable about pollen analysis is that it allows archaeologists to track the spread of viticulture across the region.

The pollen record shows a clear progression of grape cultivation moving inland from the coast, corroborating our earlier discussions about the Greeks' coastal focus and the Romans' inland expansion. Moreover, pollen analysis has helped to identify ancient grape varieties. While it's challenging to link ancient pollen directly to modern grape varieties, the diversity of Vitis pollen types suggests that multiple grape varieties were being cultivated in ancient Provence, supporting our earlier mention of the Romans introducing new grape varieties to the region.

Integrating the Evidence

When we piece together all this archaeological evidence – the wine presses and storage facilities, the amphorae and their inscriptions, and the pollen records – we get a vivid picture of wine production in ancient Provence that aligns remarkably well with the historical narrative we've explored in our previous discussions.

We can trace the progression from the early Greek coastal vineyards, with their simple rock-cut presses, to the more extensive Roman operations pushing inland, with their advanced pressing technology and large-scale storage facilities. The amphorae tell us about the thriving trade in Provençal wine, while the pollen record maps the spread of vineyards across the landscape.

This archaeological evidence does more than confirm what we know from historical sources; it brings the ancient wine industry of Provence to life in tangible ways. It allows us to visualize the ancient vintner treading grapes in a coastal press, smell the wine fermenting in a huge dolia, and imagine the ship laden with amphorae setting sail from Marseille.

Monks, Popes, and Vines: The Medieval Era of Provençal Wine

As we transition from the ancient world into the medieval period, the story of wine in Provence takes on new dimensions. The fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE marked a significant shift in Europe's political and economic landscape, and the wine industry of Provence was not immune to these changes. However, this era, roughly from 500 CE to 1500 CE, would be a crucial preservation, innovation, and expansion period for Provençal viticulture.Decline and Preservation in the Early Middle Ages

The collapse of Roman authority in Gaul led to instability and economic decline. Trade routes that had once carried amphorae of Provençal wine across the Mediterranean were disrupted, and many vineyards fell into disrepair. The sophisticated viticultural practices we discussed in relation to the Roman period were at risk of being lost.

However, during this tumultuous time, a new force emerged as the guardian of winemaking knowledge: the Christian monastic orders. Monasteries, emphasizing self-sufficiency and their need for sacramental wine, became the custodians of viticultural expertise. The Rule of St. Benedict, written in the 6th century, even specified the daily wine ration for monks, underscoring the importance of wine in monastic life.

In Provence, as elsewhere in Europe, monasteries often took over the management of existing vineyards or established new ones. They preserved the practical skills of viticulture and winemaking and the written knowledge, copying, and preserving ancient Roman agricultural texts in their scriptoria.

The Monastic Influence

As we move into the High Middle Ages, the role of monastic orders in Provençal viticulture became even more pronounced. The Benedictines and Cistercians, in particular, played a crucial role in maintaining and expanding vineyard cultivation.

The Benedictine abbey of Montmajour, founded near Arles in the 10th century, became a significant center of wine production. The monks meticulously tended their vineyards, experimenting with different grape varieties and refining winemaking techniques. Similarly, the Cistercian Abbaye du Thoronet, established in the 12th century in what is now the Var department, developed extensive vineyards. The ruins of Thoronet, with its perfectly preserved cellar, still stand today as a testament to the monastic wine tradition in Provence.

These monastic orders were not merely preserving ancient knowledge; they were innovators in their own right. They developed new viticultural techniques suited to local conditions, such as improved methods of pruning and training vines. The Cistercians, in particular, were known for carefully selecting vineyard sites, paying close attention to soil types and sun exposure – an early application of what we now call terroir.

Monastic winemakers also made significant improvements in winemaking itself. They refined techniques for pressing grapes, managing fermentation, and aging wine. The use of wooden barrels for aging wine, which would become standard practice, was largely developed and popularized by monastic vintners during this period.

The Papal Influence

The medieval era in Provençal wine history reached its zenith with establishing the Papal seat in Avignon in 1309. For nearly seven decades, Avignon, rather than Rome, was the center of the Catholic Church, which profoundly impacted the wine industry of Provence.

The presence of the Papal court, with its retinue of cardinals, diplomats, and visitors from across Europe, created an unprecedented demand for wine. This demand led to a significant expansion of vineyards throughout the region. The hills surrounding Avignon, especially in the area that is now Châteauneuf-du-Pape, experienced significant new vineyard plantings.

The Popes themselves took a keen interest in viticulture. Pope John XXII, who reigned from 1316 to 1334, established vineyards at the papal summer residence in Châteauneuf. He is credited with improving local wines' quality, possibly introducing new grape varieties and cultivation techniques.

This period also saw a revival and expansion of the wine trade. The Rhône River, an important trade route since Roman times once again became a bustling highway for wine commerce. Barrels of Provençal wine were shipped north to supply the tables of France and beyond. This trade brought wealth to the region and further incentivized the expansion and improvement of vineyards.

The papal influence extended beyond Avignon itself. Many of the cardinals established summer residences throughout Provence, each with its vineyards. These ecclesiastical estates became centers of viticultural excellence, experimenting with new techniques and grape varieties.

Lasting Legacy

Despite its initial setbacks, the medieval period proved to be a time of significant development for the wine industry in Provence. The monastic orders preserved and expanded upon antiquity's viticultural knowledge, while the Avignon Papacy created conditions for unprecedented growth and innovation.

Many vineyard areas established or expanded during this period – from the Côtes du Rhône to the hills of Var – remain important wine regions today. The emphasis on quality and site selection that began with the monastic vintners laid the groundwork for the AOC system that would emerge centuries later.

The medieval period solidified wine's place in Provençal culture. From the monks' daily ration to the grand feasts of the Papal court, wine was an integral part of daily life and celebration. This cultural significance, as much as the viticultural expertise developed during this time, is a crucial part of the legacy of medieval Provençal winemaking.

From Renaissance to Revolution: The Evolving Landscape of Provençal Wine

As we move from the medieval period into the era spanning from the Renaissance to the French Revolution (1500-1800), the wine industry in Provence entered a phase of significant expansion, coupled with new challenges. This period saw the growth of viticulture beyond ecclesiastical control, the flourishing of trade, and the emergence of new threats to wine production.

Expansion of Viticulture

Building upon the foundations laid during the medieval period, viticulture in Provence experienced substantial growth from the 16th to the 18th centuries. This expansion was driven by several factors, chief among them the increasing population and rising demand for wine.

As towns and cities grew, so did the thirst for wine. Wine was not just a luxury but a daily staple, often safer to drink than water. This growing demand led to the expansion of vineyard areas. Lands previously considered marginal for grape growing were now being cultivated. New vineyards were planted in the hills of the Var, the plains of the Vaucluse, and the slopes of the Alpes-Maritimes.

This period also saw the introduction of new grape varieties to Provence. As trade routes expanded and knowledge spread during the Renaissance, vintners began experimenting with grape varieties from other regions. For instance, it's believed that Syrah, now an essential variety in many Provençal red wines, was introduced to the area during this time, possibly from the Northern Rhône.

The expansion of viticulture also led to a diversification of wine styles. While the region had long been known for its rosé wines, as we discussed in earlier essays, this period saw an increase in the production of red wines, particularly in inland areas. The introduction of new varieties and the exploration of different terroirs contributed to this diversification.

Trade and Commerce

The growth of viticulture in Provence was closely tied to the expansion of trade. Marseille, an important port since ancient times, as we explored in our discussions of Greek and Roman influence, reached new heights as a wine trading hub during this period.

The port of Marseille became a crucial link in the Mediterranean wine trade. Ships laden with barrels of Provençal wine set sail for destinations across Europe and beyond. The reputation of Provençal wines, particularly the robust reds from inland areas and the pale wines from coastal vineyards, began to spread.

This period saw the development of new trade routes. While sea trade remained important, river trade along the Rhône also flourished. Barges carried Provençal wines northward, supplying the growing markets of Lyon and Paris. This trade brought wealth to the region and helped spread the reputation of Provençal wines throughout France.

The 17th and 18th centuries also saw the rise of the wine merchant as an influential figure in the Provençal wine trade. These négociants, based in Marseille and other towns, played a crucial role in buying, blending, and selling wines. Their activities helped to stabilize the market for growers and expand the reach of Provençal wines.

Challenges and Setbacks

Despite the overall growth and prosperity, this period was challenging for the Provençal wine industry. The religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly the Wars of Religion between Catholics and Protestants, significantly impacted wine production in parts of Provence.

Vineyards were often caught in the crossfire of these conflicts. Armies moving through the countryside would requisition or destroy wine stocks, and ongoing insecurity made it difficult for vintners to tend their vines properly. Some vineyard areas, particularly in the Luberon and Ventoux regions, saw periods of abandonment during the height of these conflicts.

The 18th century brought challenges in the form of vine diseases and pests. While the catastrophic phylloxera epidemic was still in the future, Provençal vineyards faced other threats. Outbreaks of powdery mildew, for instance, could devastate harvests. The spread of such diseases was facilitated by the increased movement of plant material between regions, an unintended consequence of the trade growth.

Climate also played a role in the fortunes of Provençal vintners during this period. The 17th century, part of what is now known as the Little Ice Age, saw cooler temperatures that sometimes made it difficult to ripen grapes, particularly in marginal areas. This likely contributed to focusing on hardier varieties and producing more robust wines that could withstand long-distance transportation better.

Despite these challenges, the Provençal wine industry showed remarkable resilience. Vintners adapted to changing conditions, experimenting with new varieties and techniques. The diversity of Provence's terroir, which we've touched upon in earlier discussions, proved to be an asset, allowing production to shift to more suitable areas during difficult times.

Conclusion

The period from the Renaissance to the French Revolution was a time of significant change for the Provençal wine industry. Building upon the monastic traditions we explored in our medieval period discussion, viticulture expanded beyond the control of the church, becoming a key part of the region's commerce and identity.

The growth in trade, mainly through the port of Marseille, helped to spread the reputation of Provençal wines far beyond the region's borders. At the same time, introducing new varieties and exploring new terroirs led to diversifying wine styles, laying the groundwork for the wide array of Provençal wines we enjoy today.

Yet this period also reminds us of viticulture's vulnerability to external forces—be they human conflicts or natural threats. The resilience shown by Provençal vintners in the face of these challenges is a testament to the region's deep-rooted wine culture.

As we conclude our journey through this era, we can appreciate how each period we've explored – from the ancient Greeks and Romans, through the medieval monastic traditions, to this age of expansion and trade – has contributed to the rich tapestry of Provençal wine culture. The stage was now set for the dramatic changes that the modern era would bring to the vineyards of Provence.

The Modern Renaissance of Provençal Wine: Challenges, Innovations, and Triumphs

As we enter the modern era of Provençal winemaking, we witness a period of profound challenges, remarkable resilience, and, ultimately, a renaissance that has elevated the region's wines to its current status as a world-leading producer of quality wines, particularly rosés.

19th Century Challenges: The Phylloxera Crisis and Its Aftermath

The 19th Century brought unprecedented challenges to the wine industry of Provence, as it did to all of Europe. The most devastating of these was the phylloxera crisis. Phylloxera, a microscopic aphid that feeds on vine roots, was inadvertently introduced to Europe from North America in the 1860s. By the 1870s, it had reached Provence, wreaking havoc on the region's vineyards.

The impact of phylloxera on Provence was catastrophic. Vineyards that had thrived for centuries were decimated within a few years. The pest's arrival marked the end of an era in Provençal viticulture, effectively wiping out many of the ancient varieties and vineyard sites we've discussed in our previous essays.

However, this crisis also sparked a period of innovation and adaptation. The solution, eventually, came from the pest's homeland: American vine species that had evolved alongside phylloxera were resistant to it. Provençal vintners, like their counterparts across Europe, began the painstaking process of replanting their vineyards using European vines grafted onto American rootstocks.

This replanting effort fundamentally altered the viticultural landscape of Provence. It provided an opportunity to reassess grape varieties and planting locations. Many ancient local varieties, unfortunately, were lost in this process. However, it also allowed for the introduction of new varieties better suited to changing market demands and modern winemaking techniques.

Early 20th Century: Cooperation and Appellation

In the early 20th Century, Provençal winemakers banded together amid economic challenges. The formation of wine cooperatives became a significant trend. These cooperatives allowed small growers to pool their resources, sharing the costs of winemaking equipment and marketing efforts. Many of these cooperatives, such as those in Bandol and Cassis, continue to play an important role in Provençal wine production today.

This period also saw France's appellation system's beginnings. In 1936, Cassis became the first Provençal wine region to receive appellation status. This marked a crucial step in recognizing and protecting the unique qualities of Provençal wines, a theme we'll see develop further in later decades.

Post-World War II Era: Quality Focus and the Rise of Rosé

The years following World War II significantly changed the Provençal wine industry. There was a marked shift from quantity to quality in wine production. The region, which had long been known for producing bulk wines, began to focus on crafting higher-quality products.

This shift was aided by technological advancements in winemaking. For instance, they introduced temperature-controlled fermentation, which allowed for better preservation of delicate aromas and flavors, significant for white and rosé wines. Improved pressing techniques and the use of inert gases to protect against oxidation also contributed to higher-quality wines.

During this period, rosé wine emerged as a Provençal specialty. While Provence had a long history of producing pale wines, as we discussed in our exploration of ancient winemaking, it was in the post-war years that the modern style of dry, pale rosé was perfected. Provence's climate and traditional grape varieties proved ideal for producing this style of wine, which would become the region's signature product.

Late 20th Century to Present: AOC Refinement and Global Recognition

The latter part of the 20th Century saw the continued development and refinement of Provence's Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system. Building on Cassis's early example, other Provençal wine regions gained AOC status: Bandol in 1941, Côtes de Provence in 1977, and Coteaux d'Aix-en-Provence in 1985, among others. These appellations helped codify the unique characteristics of each Provençal wine region, protecting traditional practices while allowing for innovation.

At the turn of the millennium, Provençal wines, particularly rosés, have gained unprecedented international recognition. The pale, dry style of rosé pioneered in Provence has become a global phenomenon, with Provençal producers leading the way in quality and marketing. This success has brought significant investment to the region, both from local producers expanding their operations and international wine companies seeking a foothold in this booming market.

There has been a growing emphasis on terroir and sustainable viticulture in Provence recently. Many producers are moving towards organic and biodynamic practices, seeking to express their specific sites' unique characteristics while protecting the environment. This focus on sustainability is not just about wine quality but also about preserving the stunning Provençal landscape that has inspired winemakers for millennia.

A Legacy Renewed

Despite its challenges, the modern period has seen Provence emerge as a leader in quality wine production, particularly in the realm of rosé. The resilience shown in overcoming the phylloxera crisis, the cooperative spirit of the early 20th Century, the post-war focus on quality, and the recent emphasis on terroir and sustainability all reflect the deep-rooted wine culture of Provence.

Provence's Historical Wine Producers

As we've explored in our historical journey, the sun-drenched hills and fragrant garrigue of Provence have been home to vineyards for over two and a half millennia. Today, the region is home to numerous exceptional wine producers who continue to build on this rich heritage while pushing the boundaries of quality and innovation. Let's explore some standout Domaines and Châteaux that have helped elevate Provençal wines, particularly rosés, to world-class status.

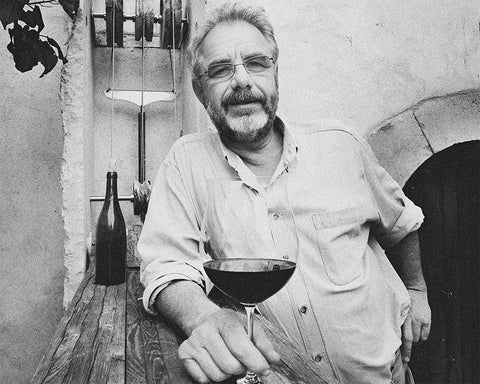

Château d'Esclans

No discussion of top Provençal producers would be complete without mentioning Château d'Esclans. Located in the heart of the Côtes de Provence, this estate has been instrumental in changing global perceptions of rosé wine. Under the guidance of Sacha Lichine, who acquired the property in 2006, Château d'Esclans has produced "Whispering Angel," a rosé that has become synonymous with the elegant, pale style that defines modern Provençal rosé.

Beyond their entry-level offering, Château d'Esclans produces premium rosés like "Garrus," often referred to as the world's most expensive rosé. These wines demonstrate the potential for complexity and ageability in top-tier rosés, challenging preconceptions about the category.

Domaines Ott

With a history dating back to 1896, Domaines Ott has long been a standard-bearer for quality in Provence. This producer comprises three distinct estates: Château de Selle and Clos Mireille in Côtes de Provence and Château Romassan in Bandol. Each estate produces wines that reflect its unique terroirs, from Château de Selle's schist soils to Château Romassan's limestone.

Domaines Ott is particularly renowned for its rosés, which are presented in distinctive amphora-shaped bottles—a nod to the ancient history of winemaking in the region we discussed in our earlier essays. Their wines are known for their freshness, complexity, and ability to age gracefully.

Château Minuty

Located on the Saint-Tropez peninsula, Château Minuty has been family-owned since 1936 and has played a significant role in establishing the reputation of Côtes de Provence wines. In 1955, the estate was one of the original 23 estates to be designated as Cru Classé in Provence, a testament to its consistent quality.

Minuty is known for producing a range of rosés, from their fresh and approachable "M de Minuty" to their premium "281" cuvée. The latter is a single-vineyard rosé that showcases the potential for site-specific expression in Provençal rosé.

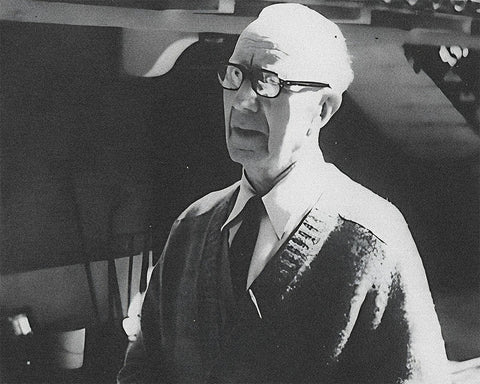

Domaine Tempier

When discussing the red wines of Provence, Domaine Tempier in Bandol is often regarded as the benchmark producer. Established in 1834, this estate was instrumental in reviving the Bandol appellation in the mid-20th Century under the leadership of Lucien Peyraud.

Domaine Tempier's red wines, based primarily on the Mourvèdre grape, are known for their power, complexity, and longevity. Their rosés, while less famous than their reds, are also considered among the finest in Provence. The estate's commitment to traditional winemaking methods and organic viticulture has made it a favorite among wine purists.

Château de Pibarnon

Another star of the Bandol appellation, Château de Pibarnon, is perched high in the hills overlooking the Mediterranean. The estate's unique terroir, with its high-altitude vineyards and limestone soils, produces wines of distinctive character and finesse.

Like Tempier, Pibarnon is renowned for its red wines, which showcase the full potential of Mourvèdre when grown in optimal conditions. Their rosés are also highly regarded and known for their structure and ability to complement various cuisines.

Clos Cibonne

Located in the Côtes de Provence appellation, Clos Cibonne stands out for its dedication to the Tibouren grape variety. This ancient variety, which we touched upon in our discussions of Roman influence on Provençal viticulture, is rarely seen outside of Provence.

Clos Cibonne's rosés, made primarily from Tibouren, are distinctive for their coppery hue and savory character. The estate ages their rosés in large old oak foudres, a practice unusual in Provence, resulting in wines of remarkable complexity and ageability.

Château Simone

Château Simone, located in the tiny Palette appellation near Aix-en-Provence, is a unique producer that defies many conventions of Provençal winemaking. This historic estate produces white, red, and rosé wines, with its white wines being particularly celebrated—a rarity in a region dominated by rosé production.

The estate works with several rare local varieties, preserving a piece of Provence's viticultural heritage. Their wines are known for their complexity and ability to age, with the whites, in particular, capable of developing in the bottle for decades.

A Growing Wine Scene

These producers represent just a small selection of the outstanding Domaines and Châteaux that call Provence home. Each, in its way, embodies the rich history and bright future of Provençal wine that we've explored throughout our discussions.

From Château d'Esclans' role in elevating the global status of rosé to Domaine Tempier's preservation of traditional Bandol winemaking, these producers showcase Provence's diversity and quality. They demonstrate how the region has built upon its ancient viticultural heritage – which we traced from the Phocaean Greeks through the Roman era and beyond – to produce thoroughly modern wines yet deeply rooted in their unique terroir.

As the wine world evolves, these producers and others like them ensure that Provence remains at the forefront of quality wine production, particularly in rosé but increasingly in reds and whites.